12 Factor Compliant Terraform CI/CD

I love terraform open source for managing infrastructure as code. The ability to track state and manage the lifecycle of my infrastructure over time is a huge advantage over the cloud specific languages available from the major providers (eg. ARM and CFT). But there is one particular aspect that I struggle with when implementing terraform at scale: defining an effective CI/CD model. As a twelve factor purest I want strict separation between my build and release phases. I also tend to be pretty opinionated about my DevOps pipeline. I like tools that are narrowly scoped and easily composable within a build and release orchestrator of my choice.

Factor V

I feel obligated to acknowledge that the 12 factors were created as a framework for designing applications targeted at APaaS runtimes. But as we move away from managed hardware and into a cloud platform world, we are deliberately adopting ALM practices for managing that cloud infrastructure as well. In short our infrastructure is no different than our applications and should be managed using the same principles.

Factor V declares that you should strictly separate the build, release and run phases of your application lifecycle. The build should produce a versioned, environment agnostic artifact and place that into some central repository. The release phase then takes that artifact, combines it with the environment configuration(s) and deploys the resulting composite into the target environment(s), applying workflow logic to model the SDLC and ITIL practices of the organization.

An important implied outcome of this model is that I should be able to easily rollback to a previous version of my application by simply redeploying a previous build. Since a deployment contains everything needed to produce a specific version of the running application: artifact + configuration.

plan != build

It is really important to recognize that a terraform plan is not stateless. The plan is produced by taking both the declared expectation (the terraform files) and the current state of the platform/infrastructure. Terraform then calculates the difference between the expectation and the current state. The output plan contains only those actions needed to transform the current state into the target expectation. This model has several important impacts on how we should manage our build and deploy workflows.

On the one hand having a deterministic plan that we can clearly understand is the holy grail of traditional change management organizations. You know exactly what changes the plan is going to enact and regardless of who runs it or when, the plan will not change. You can easily generate a plan, attach it to a change ticket and send it off to run the gauntlet of approvals where each person can inspect the plan and feel safe that nothing will happen that isn’t called out in explicit detail.

But what about modern agile, cloud native organizations? In my experience, large cloud platform implementations rarely stand still for any length of time. In a fast moving environment where multiple teams are managing cloud infrastructure, the current state of the platform may change a dozen times before all of the needed approvals are gathered for a specific change. While terraform is smart enough to make the generated plan itself idempotent, this should not be confused with treating the full scope of the definition as being idempotent.

Make it so!

So how do we get the best of both worlds: A deterministic process that can account for the fluid nature of an active cloud environment and a well governed delivery pipeline that allows us to feel confident that we understand the change and can detect and respond to any aberrant behavior along the way.

Note: Hashicorp publishes an excellent guide on using terraform in automation as well as an in-depth series of articles on terraform best practices. The process I describe below is a modified version of the model presented in those resources.

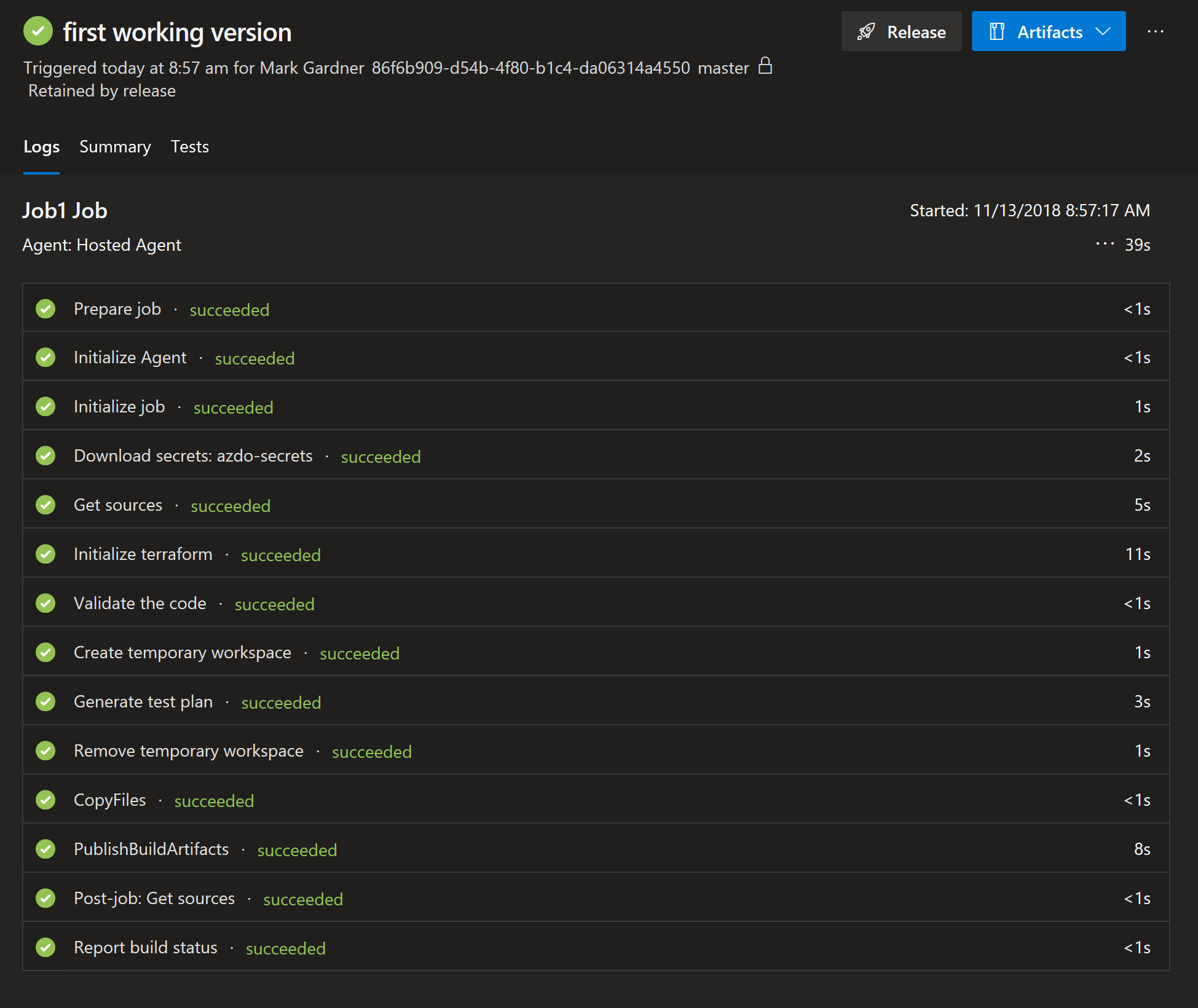

Building an artifact

Many infrastructure as code (IAC) tools skip the CI phase, opting to connect the code repository directly to the release workflow. The argument for this model is generally something along the lines of “CI is a tool for compilable code and IAC isn’t compilable”. To me this misses the point of CI; to quickly provide high-value feedback directly to the developer. The simple fact of “does it build” is generally accepted as the first and most basic test of any code change. Even though IAC may not compile, all of the major flavors offer an activity that is analogous to the compilation phase of an application. The trick is figuring out how to maximize the value of the feedback we can derive from those activities.

Resolve Dependencies: terraform init

When you init your local workspace terraform downloads all referenced modules and providers and copies them into the local .terraform folder. These are all versioned artifacts that have a point-in-time relationship with the infrastructure you are building. If you were to re-init the same code at a later point in time you would very likely end up with a different result as some of those dependencies would have moved to later versions. You could control this by using strict version constraints on all of your provider and module references, but this can lead to increased code churn and frustration in the development stage. Instead I am in favor of using major version constraints and allowing the pipeline to use the most recent minor + patch version available. We can then satisfy the requirement for reproducibility by bundling the dependencies into the artifact at the end of the build.

Lint: terraform validate

Now that we have gathered all of the necessary components, the next step is to simply validate the syntax. This is the most basic and fastest validation that can be performed. It guards against those “simple” changes that are so trivial the developer is confident nothing could go wrong…until it does. We are all guilty of making quick edits to code and blindly checking them in without doing the due diligence of a quick build and test on our local workstation. How many times have you forgotten a semicolon or misspelled a keyword only to learn about it 5 minutes later when the build breaks?

Build: terraform plan

If the syntax is valid, then we should attempt to “build” the code. This is where things get interesting. As noted above, terraform doesn’t compile in the traditional sense. The plan is the closest analog to a compiled artifact we have. But to generate a plan we have to connect to an environment and provide configuration values, which is the responsibility of the release pipeline and we don’t want to blur the line between CI and CD.

My solution is to create an empty workspace and generate a plan with generic configuration. The goal of this is simply to generate a plan that exercises every resource defined in code. This plan will not be run against any of the environments in our release pipeline. The mere fact of its successful generation is just another validation in our CI pipeline. This confirms that we didn’t make any logic errors in our code: cycles, nonexistent references, invalid interpolations.

Unit Test: terraform show --json

Update 8/15/2019: The release of terraform 0.12 introduced the ability to export a plan to JSON which completely changed my approach to unit testing. This section has been updated to reflect this change in methodology

Just like with application code, an IAC developer will invariably make certain assumptions about the behavior of the code at runtime. And just like with application code, it is a good idea to validate that those assumptions hold up under a variety of scenarios. Unit testing is a tried and true methodology for documenting and enforcing those assumptions. The tests provide a set of guardrails that ensure that as the code grows more complicated and incorporates new functionality and scenarios we don’t lose sight of the overall goal of the solution.

Infrastructure code tends to have many nested dependencies: resource A depends upon resource B depends upon resource C. This can be particularly troublesome as a simple error or change to one resource can have exponential impact to resources elsewhere on the dependency graph. A well defined unit test suite will help protect against a cascade of unintended consequences. Prior to terraform 0.12 unit testing was an in-exact science with no solution that was truly satisfying. But with the release of 0.12 it is now possible to export the plan as a machine-readable json document. This makes it possible to write very clear and dependable unit tests that validate expectation against the execution.

Here is an example of a simple unit test that validates the interpolated address space of a dynamically created subnet:

public class PlanTests {

private static string planPath = "plan.json";

private dynamic plan;

private IList<dynamic> resources;

public PlanTests () {

var rawPlan = File.ReadAllText(Path.Combine(Environment.CurrentDirectory, planPath));

plan = JObject.Parse(rawPlan);

resources = new List<dynamic>(plan.resource_changes);

}

[Fact]

public void Test()

{

var r = resources.Single(p => p.name == "app-sn");

Assert.Equal("10.0.0.32/27", r.change.after.address_prefix.Value);

}

}

Publish the artifact

At this point we have done all of the basic validations we typically associate with the CI phase. The final step is to produce a stateless, versioned artifact which can be fed into our CD pipeline. To do this we simply bundle up all of the code files plus the .terraform folder which contains the dependencies resolved at during the init, tag the bundle with our current version number and push it to our artifact repository of choice.

You can find the code for the above pipeline here.

You can find the code for the above pipeline here.

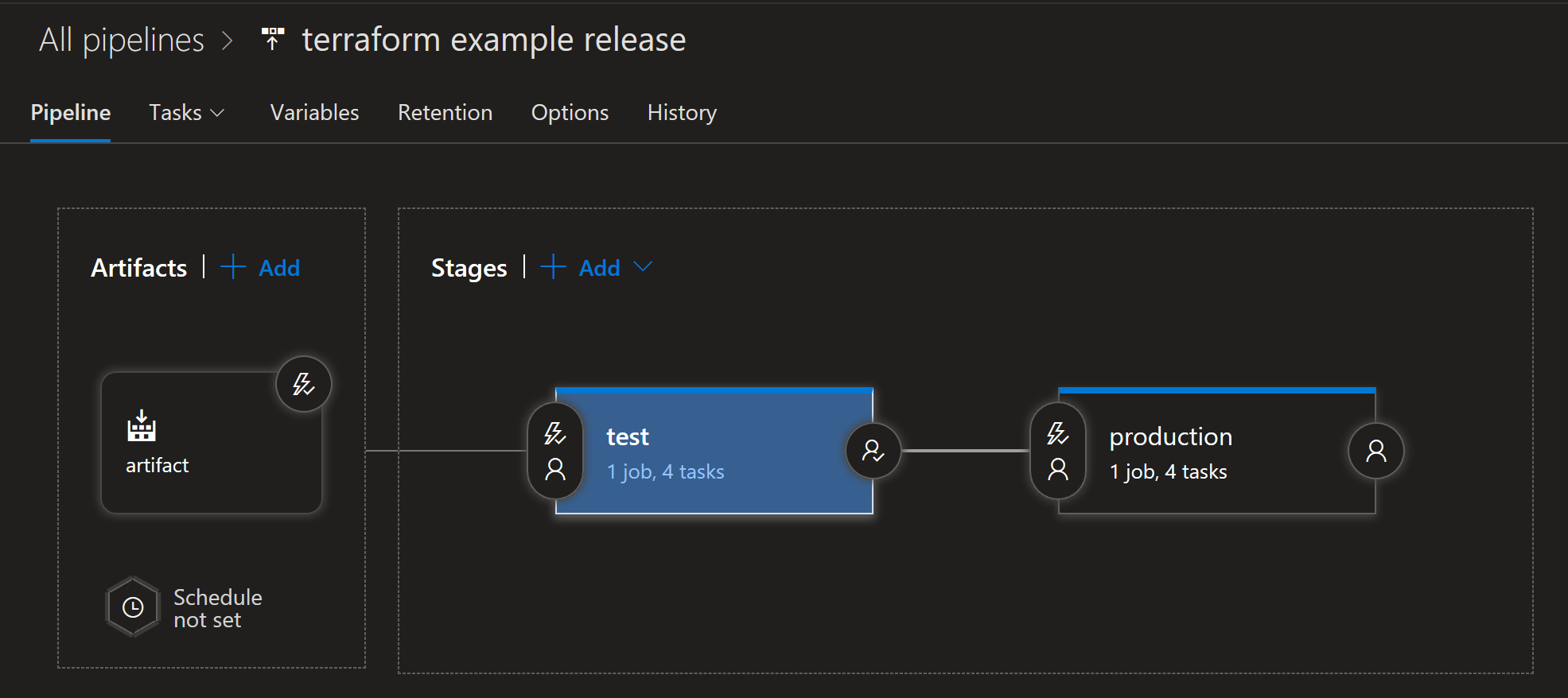

Deploying across environments

Now comes the easy part, deploying our artifact into our target environments. For the most part this is pretty much in-line with the practices outlined by Hashicorp. There are three main differences:

- Rather than attaching the release pipeline to our git repo, we use the bundle produced by the build stage as our source.

- Because we bundle the dependencies into the build artifact, we do not need nor want to re-initialize during deployment.

- Our deployment will build a new plan for each environment and immediately deploy it, ensuring that we are enforcing the full definition against the environment with each deployment (as opposed to a stale plan that was generated non-contemporaneously).

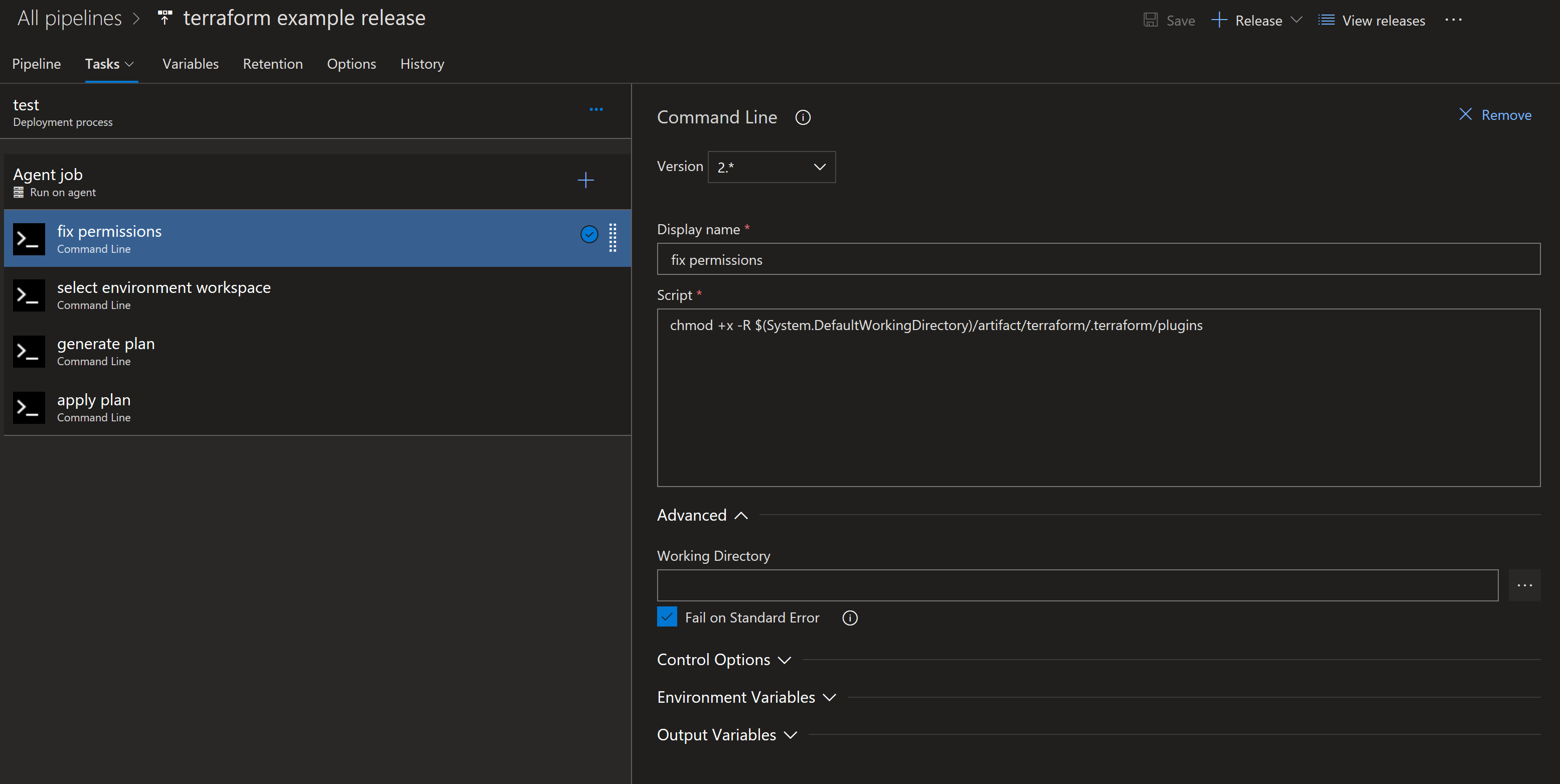

Fix Permissions

This may be a platform specific issue, but on Azure DevOps any files that are downloaded externally are defaulted to mode 444 (read-only). This creates a small problem as terraform needs to be able to execute the provider in order to generate and apply the plan. This is easy enough to fix with a simple chmod u+x -R .terraform/plugins/

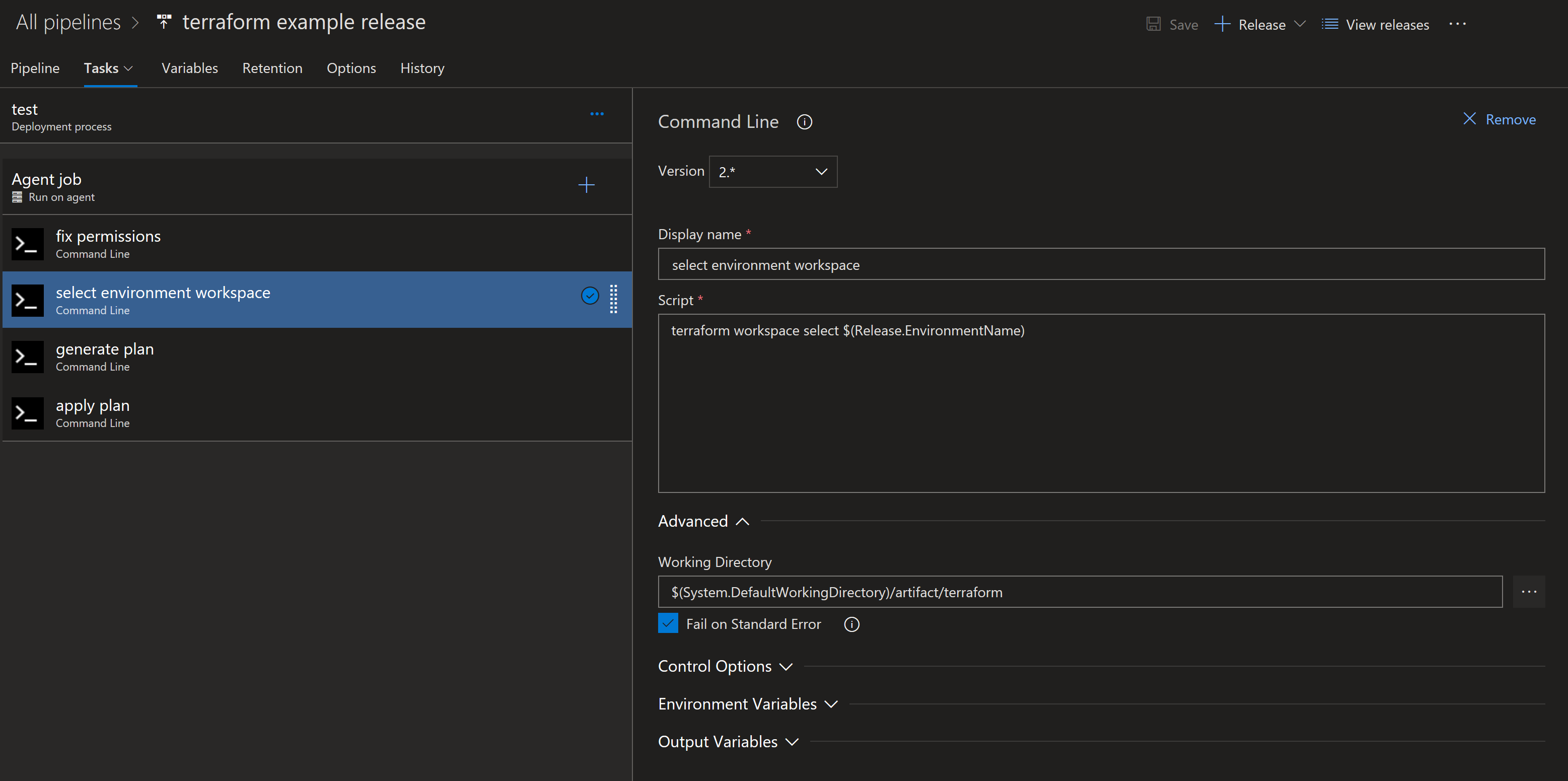

Select Workspace

Each environment in your release pipeline should have it’s own workspace in your terraform state store. As you progress through the environments you want to make sure you are acting on the correct environment.

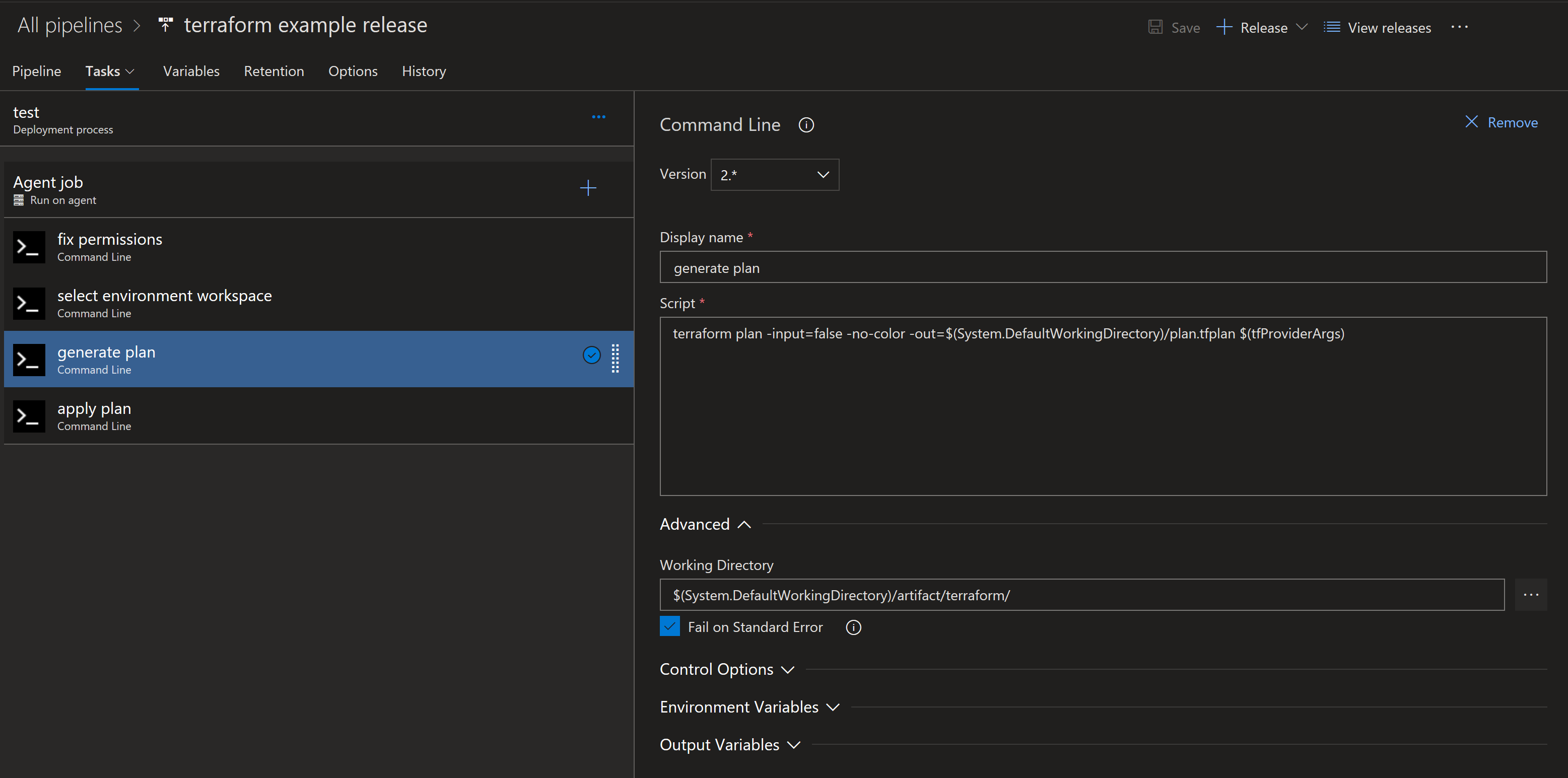

Generate an environment specific plan

This is where we inject our environment specific configuration, either through a var file or command line arguments. The resulting plan will generate all of the actions necessary to bring that specific environment into compliance with the desired state defined in the terraform code. It bears repeating that the plan generated at this point is only valid for this specific environment.

Optional: Manual Intervention

This step is something that you may want to implement early on while you are building confidence in the automated pipeline. It can be intimidating to cede complete control over your infrastructure to a fully automated system and some organizations will want to inject human oversight into the process as a safety mechanism. To that end you can add a manual intervention step between the plan generation and application steps. This will allow you one last “are you really, really, really sure?” moment prior to any changes being inacted. If you opt for this path, you’ll want to publish your pipeline artifact (the plan), pause for the plan to be inspected and approved and then resume with the apply action once the approval is received.

If you opt for this route you want to keep the time interval as short as possible. The longer the plan is waiting on approval, the more out of touch it will become with the current state of the platform. At some point you will want to expire the plan and restart the deployment from the beginning.

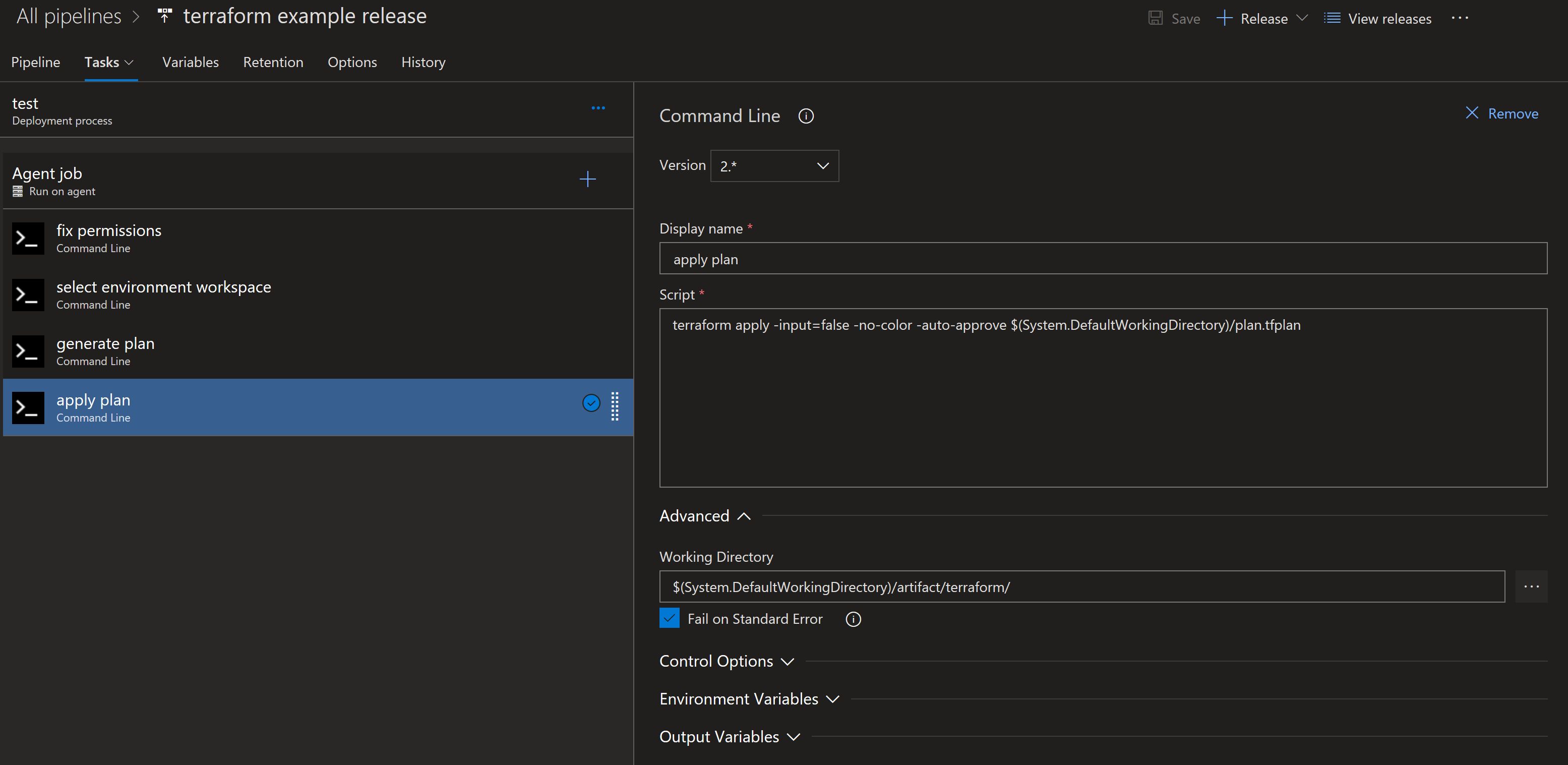

Apply the plan

Now it’s time to actually do something! At this point we have a valid plan and a high level of confidence that it is going to successfully deploy. So fire away! Keep in mind that some platform changes can take a long time to deploy. You may want to set a fairly long timeout on this particular activity so that the platform doesn’t terminate it while it’s waiting on a particularly complicated resource to spin up. Any failures that happen at this point should be routed back to the committing developer for review.

Integration testing

I won’t dwell too much on this as there is plenty of documenation out there on how you should or should not do integration testing. Mainly I just want to point out that this is where it should go in your release pipeline. Once the apply has completed, you should run your integration tests against the environment to validate the configuration.

Rinse and repeat

The process for deploying to all subsequent environments should be identical to the first. Simply multiply the template by the number of environments in your pipeline. Each subsequent successful deployment should further bolster your confidence that everything is working as it should and that the final production release will be a non-event.

Rolling back

In the event that you find your environment in an inoperable state post deployment, recovering should be a straight-forward exercise. Simply redeploy the previous version from your artifact repository. Because the artifact contains the full definition and all of it’s dependencies, it should faithfully recreate the desired state without any hiccups.

Additional Considerations

If you are using a remote state store (and you should be), running terraform init may put some sensitive information into the .terraform folder. In my case I am using an Azure blob container as my state store and the access key is visible in cleartext. You should assess the security implications of putting this information into artifact repository and take appropriate precautions according to your organizations requirements.

I like to automate as much toil out of my work as I possibly can. One particularly exciting example of this is in the release gates for my terraform workflows. In Azure I configure all of my resources to dump their diagnostic and metric data into a common log analytics workspace. This makes it easy for me to build a simple query that looks for errors being generated anywhere within the platform. For the purpose of gating my releases I have an Azure monitor alert that triggers on any significant increase in the variance of the number of errors being observed. The idea is that if a change introduced by my IAC pipeline correlates with a localized spike in the number of errors on the platform, I want to pause my rollout until I can investigate and determine whether the change has caused the spike.

One final suggestion I will add is the creation of a compliance build/release. The plan command has one really handy switch: --detailed-exitcode. When called with this switch terraform will throw a non-zero exit code in the event of a non-empty diff, meaning that if it detects any difference between the provided state and the target environment the execution will error and fail the build/release. This very useful feature can be used to run a scheduled deployment against your environments (I recommend daily) to tell you if there has been any configuration drift in that environment. This can be a lifesaver for detecting changes made outside of the pipeline by operational teams, security remediation or rogue admins.

References

The code I used to demonstrate this pipeline, including the Azure DevOps build pipeline, is available here. A multi-stage pipeline implementation which includes the release definition can be found here (note that this feature is still maturing and so the defined pipeline is still a bit raw).